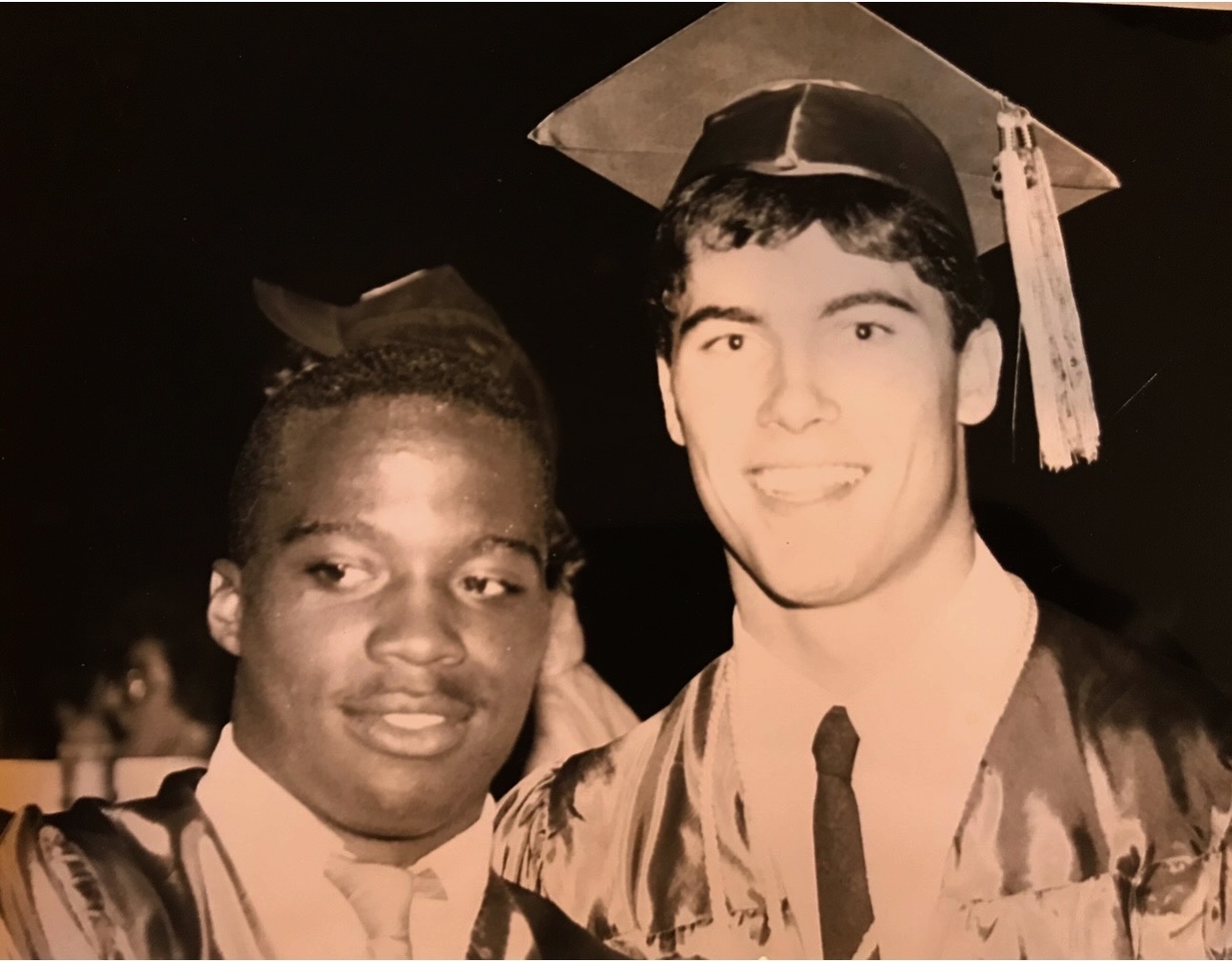

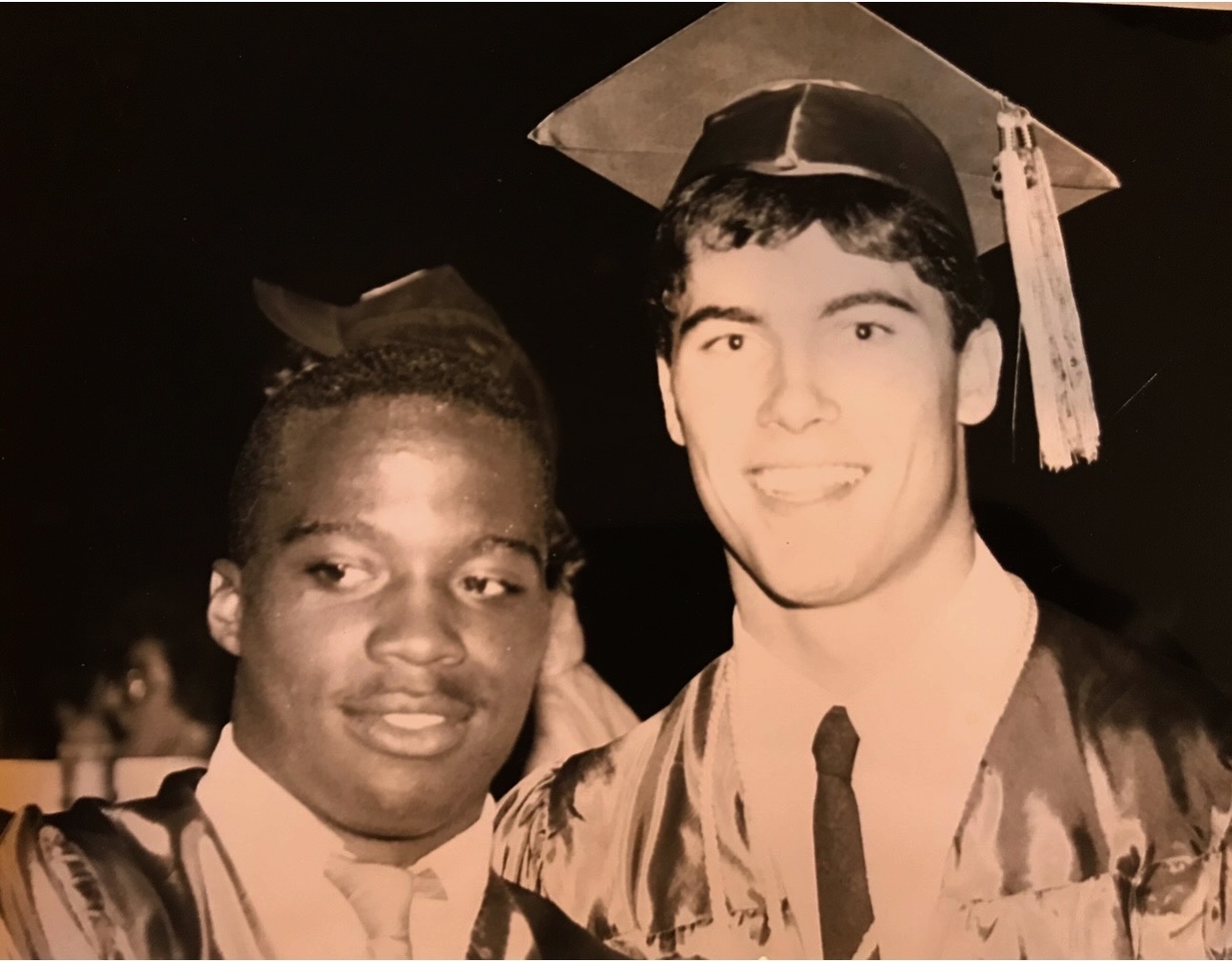

Walter Bailey & Matt Asay

It had been a long time since Matt Asay had spent any quality time with the friend he’d been virtually attached at the hip to since childhood. Something like three years and change it was, but it seemed even longer to Asay, who was painfully aware of the personal struggles Walter Bailey had been going through during that time and well before it.

The two had spoken by phone, even had lunch a couple times. But after each occasion, Bailey would go quiet again, changing his phone number and slipping back into the latest dark place from which he had temporarily emerged.

And while Asay never gave up hope that he and his friend would eventually get back together for good, up to this point he hadn’t wanted to push it. He'd been working hard to conquer some demons of his own and wasn’t ready for a permanent reunion until Bailey was ready to face up to his.

But now he was feeling confident enough in the progress he'd made to believe he could be a positive influence on Bailey without himself being influenced by what his friend might be up to.

So it came to be that Asay found himself sitting in his car in front of a drug house in northeast Portland, squinting through the scorching summer sun, trying to determine if the overly thin guy heading up the street, face partially obscured by a beard and hoodie, really was the man he called his brother.

Friendly Rivals

There are infinite ways to start a lifelong friendship, and who knows how many of them involve rough housing and toy action figures. But at least one did.

Asay and Bailey met in 1978 at Sacajawea Elementary School, where the former had been enjoying his status as the unrivaled alpha-puppy of the lower grade levels right up to the day the latter swaggered in from Woodland Park.

“I was kind of a hot shot-athlete in kindergarten and first grade,” Asay remembers with a laugh. “But when Walt transfers in, it became clear pretty quickly that he was kind of a hot shot, too, and now he’s encroaching on my territory. So on the day we met, we went out on the field and had a foot race. And, of course, he blew me away.”

Despite his dominant win, Bailey saw in Asay a worthy athletic rival. But as the uncomfortable new kid in school, he also identified something more meaningful to him.

“I was a very unassuming, kind of awkward kid who’d been growing up with friends who were all black,” Bailey says. “Now I’m at a different, predominantly white school trying to forge new relationships. And I quickly saw that Matt was a kid who was, yes, athletic, but also someone who had a good influence on other kids. So, I looked up to him because of that.”

As Bailey began to settle into his new school, he became friendly enough with Asay to snag a coveted invitation to his eighth birthday party.

“I think my mom probably got some gift ideas from his mom and I wound up giving Matt a Star Wars action figure,” Bailey recalls. “I loved Star Wars, but it turned out Matt loved Star Wars even more. So, we formed an instant connection right then.”

Bailey began staying overnight at Asay’s house on a regular basis, which gave them the opportunity to cement their friendship by bouncing each other off Asay’s bedroom walls like future pro wrestlers.

“Matt had this tiny room with his bed right up against the window,” Bailey says. “We’d play tackle football in there, and to score you had to dive on the bed and touch the wall with a Nerf football. We’d give each other black eyes, knots on the head and scratches because we were both so competitive. That’s when I knew this guy was a lot like me -- only bigger. And we just became best friends.”

Which is not to say the two stopped competing against each other as they advanced through the grades regardless of the sport they were playing. And they both played most of those available to them, including football, basketball, baseball, soccer and, in Bailey’s case, track.

Oh, and roller skating, too. Can’t forget roller skating. Bailey certainly can’t.

“Matt and I would go to Skate Palace every Saturday,” he says. “All the kids from the ‘hood would go. Whenever they had couples skate, all the girls would come get Matt because he was so handsome and nice, and I was left with nothing!”

Benson or Bust

While Asay grew up a short bike ride from Madison, and both his parents were alums, he had always planned to follow two uncles to Benson. “Getting my acceptance letter there was probably one of the happiest days of my life,” he says.

Bailey was raised in the Jefferson district with a sister and four older brothers, three of whom went to Benson. Brother Tracey played with AC Green on the school’s 1981 state championship basketball team. Bailey says that, while he never felt any family pressure to go to Benson, “since my brothers went there, I had been able to see what it was about. So, I just naturally gravitated there.”

While he and Asay were happy to know they wouldn’t be separated in high school, there was an “incident” after they said goodbye to Gregory Heights Middle School that left some doubt whether they’d even be speaking to each other by the time they enrolled at Benson. Neither of them can relate the story now with a straight face, but it was no laughing matter back then.

Here’s Asay’s take on the story:

“That summer Walt and I took part in a basketball camp at Concordia College. At the conclusion of it, they held a one-on-one tournament, and we both made it to the semifinals. Now we’ve got to play each other. Everyone thought he was going to blow me away, including, I think, Walter. But I was starting to come into my own in basketball and wound up beating him. He wouldn’t talk to me for the rest of the summer.”

Now Bailey’s spin:

“Matt was smart enough to realize, if he lets me get the ball first, I’m going to out-point him. Because I could shoot. So, he gets the ball first and, because he’s taller, just backs me down and shoots over me. Over and over again. After he beats me, I ran home and cried. I was so upset. I couldn’t believe my best friend beat me one on one in front of everybody. He beat me in front of everybody!”

“He was so bent out of shape, he wouldn’t return my calls,” Asay adds. “We were going to be playing football together as freshmen, and he didn’t talk to me until maybe two weeks before daily doubles started. Then we connected and everything just melted away. He just needed some time to process not always being better than me…”

“...not being king,” Bailey interjects, laughing. “I was immature in a lot of ways, and Matt grounded me.”

Shining Stars

He jokes now about the king thing, but Bailey certainly came close to earning that status at Benson. In his earliest days in sports, Bailey’s first love had been track. But once at Benson, he identified a phenomenon that quickly had him rearranging his athletic priorities.

“I was intrigued by the people who got the most attention in sports, and football and basketball players were those people,” Bailey says, laughing.

Bailey remained committed enough to track to earn four letters and claim state championships in the long jump and as a member of Benson’s mile-relay team, but his heart belonged to football and basketball. On the field, he was named 1st Team All-PIL and All-State as both a running back and defensive back and, in basketball, he made 1st Team All-PIL as a guard.

Not one to be outdone by his friend, Asay earned three letters in football and, as a senior, 1st Team All-PIL status at tight end, defensive end and punter. That same year he made the 2nd Team All-State defensive team and played in the Shrine All-Star Game.

He captained the Benson football and basketball teams and, in baseball, was honored as a 2nd Team All-PIL outfielder and pitcher his senior year.

Through Asay’s sophomore year, basketball and baseball were his strongest sports. But that changed junior year when his football career took off and his best sports memories were made, he says.

“We had really good teams my junior and senior years,” he says. “We were 8-1 and 9-0 those two years, and junior year we won three state playoff games, which was the first time a PIL team had done that in 10 or 15 years.”

On the football field, Asay and Bailey were as connected as they were off it where, Asay says, “We were thick as thieves. Anything one of us was doing, the other was doing.”

While Bailey starred as a runner, he also could throw the ball, and Asay tried several times to talk Benson’s future PIL Hall of Fame coach Bill Dressel into taking advantage of that skill.

“I’d ask him, ‘Why don’t you let Walter throw a halfback pass? Run a sweep and let him throw it to me downfield.’ I finally talked him into doing it against Jefferson junior year, and we scored a 50-yard touchdown. From that point forward we ran that play at least once or twice a game. Senior year, I probably scored 14 touchdowns, and about half came on passes from Walter.”

Both players’ athletic success earned them multiple college scholarship offers (and, later, induction into the PIL Hall of Fame – Bailey in 2005; Asay in 2023), but not from the same schools. That meant the inseparable friends would be separated for the first time since second grade.

"I never knew which dad was coming home from work -- angry dad or happy dad. It just depended on whether he'd been drinking. He was kind of a hero, but at the same time I was terrified of him." -- Matt Asay

Out of the Light, Darkness

For all the good times they had as kids, Asay and Bailey both grew up in households that were both loving and, at times, tumultuous.

“My mom, Sharon, always encouraged me to play sports and was my biggest cheerleader growing up,” Asay says. “She worked three jobs but always made sure my sister, Amy, and I made it to practice, games and school events. She was my hero and role model. My grandparents were also very supportive and were always at my games.

“But I never knew which dad was coming home from work -- angry dad or happy dad. It just depended on whether or not he’d been drinking. He was kind of a hero, but at the same time I was terrified of him. It was a confusing situation to be in as kid. Sports were kind of an escape. I could go play ball for a couple hours and it would be the best part of my day.

“But my dad never came to any of my games. I think he had some mental health issues on top of alcoholism that made it difficult for him to be out in public. And I think he felt pretty bad about some of his choices. But it hurt when I was having a lot of success and he was nowhere to be found.”

Asay's parents divorced when he was 10 and, from his sophomore year on, he says he benefited from the love and support of his stepfather, Ken Hutchens. But while he no longer was under the influence of his father unpredictable behavior, Asay’s genetics were another matter.

“I think I knew drinking was going to be a problem in middle school,” Asay says. “That was the first time I drank, and I liked the feeling alcohol gave me. It kind of took all my insecurities away. I liked the feeling so much that I just kept drinking that first time until I got sick. After that, I didn’t drink for maybe two years. Then the next three times I drank, the same thing happened.”

That was enough to scare off Asay from alcohol for another couple years. Then came college. After accepting a scholarship offer at Portland State and starting classes, Asay says, “It was kind of an eye-opener to see people drinking in the dorms on a Tuesday night. I was like, I didn’t know you could drink on a Tuesday. That’s how drinking became part of a routine for me.”

When, after two years, Asay’s PSU football career didn’t pan out, he left school. “It started feeling like a job,” he says, "and alcohol and drugs had become more important than my education or football."

By then, he was drinking four or five days a week and, when he quit football, “that’s when I start drinking more. It wasn’t like I was drinking to get smashed, but I was drinking enough to feel OK. I called myself a functioning alcoholic. I never lost a job because of drinking, but there were many times I should have gotten in trouble.”

In 1994, Asay married a girl he’d met in the dorms at PSU. Bailey was, of course, his best man. The Asays started a family (his three sons are now 24, 26 and 29) and he continued to work on building a painting business as his drinking and drug habit grew worse.

“From the ages 23 to 36, I was an everyday drinker,” he says.

That ended in 2006 when his family stepped in.

“My mom and stepdad, my sister and her husband and my grandparents staged an intervention,” he relates. “They said, ‘If you go to inpatient rehab, we will support you the entire way. If you don't go, we’re done with you. You’re killing yourself.’ They gave me tough love, and that was my wakeup call.”

Anything That Felt Good…

In the first few years after high school, Asay and Bailey still saw each other fairly frequently, and their reunions always were an excuse to party.

“Walter partied the same way I did,” Asay says. “But I never thought I had a problem, so I never thought he had a problem.”

While his football skills had earned him scholarship offers from dozens of colleges, including every Pac-10 school, before Bailey could qualify for admission to his school of choice, the University of Washington, he had to spend a year working on his grades at Western Washington in Bellingham.

Once he got to Seattle, his stellar play helped the Huskies earn a share of the 1991 national championship and three straight trips to the Rose Bowl. The All-Pac-10 cornerback’s eight interceptions in ‘91 are still third-most in the Husky record book.

To all the world, it sure looked like Bailey had set himself up for the NFL, possibly even as a first-round draft pick. But his on-field success was hiding the reality that he was depressed and suffering from anxiety and self-doubt, some of which he attributes to what he now refers to as “trauma” at home growing up.

“I had a very loving family, but there were things going on at home that I didn’t want to tell people about,” he says. “So, I bottled it up, and then it all would come out of me when I was on a football field. That was my canvas. That’s where, athletically, I was able to recreate everything that was going on inside of me, which I now know was trauma. And my aggressiveness, being so mad when we lost, those were signs of trauma that I was releasing.

“At the time, I had no idea what trauma was, but it probably started in middle school and continued into high school, then followed me to college, where I started masking things with alcohol and drugs. They provided a temporary respite from the thoughts and feelings I was having.”

Bailey injured his shoulder in the 1993 Rose Bowl, and after performing poorly at the NFL Combine, then skipping meetings NFL teams had scheduled with him, he went undrafted. He attempted to catch on with the New York Giants as a free agent but was cut after testing positive for alcohol and marijuana.

Bailey wound up playing for the Sacramento Goldminers of the Canadian Football League in 1993, but was traded to Edmonton the next year and released four days into training camp.

Things got worse from there. In a 2015 feature story in The Seattle Times, Bailey is quoted saying, “Anything that looked good, tasted good and felt good, I was trying it. I was experimenting with anything that would make me feel numb.”

Bailey couldn’t hold a job. He and a partner had a daughter in 1996, but he was in no condition to be a father, and they moved away from him two years later.

In the months leading up to the day in 2006 when Asay entered rehab, he and Bailey were partying together several times a week. Bailey was the last person Asay saw before checking in. Still in denial about his friend's troubles, Asay says he had no idea how deep they ran until he was discharged two months later. By then, even though the fog of his denials had begun to lift, he knew he was in no position to help.

“They told us in treatment that you can’t hang out with people who are still doing the same things you used to do and expect a different result for yourself,” Asay says. “So, I didn’t reach out to Walt, and he didn’t reach out to me either. My feeling is he didn’t want to jeopardize my sobriety.”

More than three years passed before the two would see each other again.

“Walt called in 2009 and was really struggling,” Asay says. “We hung out a little bit, and it was great to see him. But he wasn’t ready to seek help. It took another year before he finally hit a bottom that was deep enough for him to say, 'I’m done. I give up. Tell me what to do'.”

The Road Back

It was Bailey, the guy walking up the street dressed for fall on a 100-degree day. He’d lost 40 or 50 pounds, and the beard was a new feature, but Asay could now see it was indeed his friend, his brother heading his way – however reluctantly.

“I just knew he was thinking, ‘He’s already spotted me; I can’t get away’,” Asay remembers.

Sometimes on prior occasions when Bailey would resurface for a call or lunch, then disappear again without a trace, he would ask his friend for a lift "home." Asay started making mental notes of Bailey’s drop-off locations.

“So, after we met up in 2009 and he ghosted me again, I went looking for him back at one of those spots,” Asay says. “Of course, it was a drug house. I actually went up and knocked on the door, but no one answered.”

So Asay went back to his car and waited until, eventually, he saw Bailey, close to unrecognizable, crest the hill.

“He came up to my window and I just said, ‘Man, I love you and I’m here for you no matter what. When you’re ready, give me a call,” Asay says.

On April 28, 2010, he was dropping his kids off at school when his phone rang and an unfamiliar number appeared on the screen. As soon as he was freed up, Asay listened to his voicemail.

“It’s Walter saying ‘Matt, I’ve finally hit bottom. I’m done. Please call’,” Asay remembers vividly. “I called immediately, got the address of this drug house he was hanging out at and told him, ‘I’ll be there in 15 minutes.’ I bolted over there and helped Walter put all his possessions into a couple garbage bags, then took him back to my place. He’s been sober ever since.”

“Once the pain got to be so great, I called my best friend and he was there for me,” Bailey says. “I’m living in an abandoned house with no lights and no food, and then he comes in and I see his smile, and we hug and I felt like all the hurt and trauma just went away.”

“It brings me to tears sometimes when I think about it,” Asay adds. “I felt like I had lost my brother. I was scared he was going to die. To have him redirect his life the way he did really feels good.”

After six months of inpatient treatment at DePaul Residential Treatment Center in Portland, Bailey graduated and started attending AA meetings and, in 2012, that’s where he and his future wife, Myka, went on their first date.

The same year, Bailey went back to DePaul, but this time as an employed resource for patients. A year later, he became a certified drug and alcohol counselor at the center, and two years after that, he joined Central City Concern, an intensive outpatient program dedicated to treating African Americans with mental health and addiction issues.

Bailey now works as an operations and policy analyst at Oregon Health Authority helping “shape policy around underserved, underprivileged and minority populations.”

He's a happy father (he reunited with his oldest daughter, Brianna, 28; a second daughter, Mya, is 17) and grandfather who is committed to “giving back” to others through his work with Dynamic Athletic Solutions, a program focused on athletes and coaches and dedicated to issues related to mental health, substance abuse and diversity.

On April 30, 2025, Bailey gratefully celebrated his 15 years of sobriety with the friend he’s counted on and looked up to since second grade. Asay will celebrate his 20th year on Jan. 12, (2026).

“If Matt didn’t get sober, I just don’t know that I ever would have,” Bailey says. “But the gift he gave me was being an example of goodness and principles and having a life worth living. He showed me that I could be someone who amounts to good.”

After selling his painting business, Asay went to work as a financial advisor in 2012 and has been with Edward Jones since 2019. A grandfather of four, Asay’s three 20-something sons (he got divorced in 2007 shortly after getting sober) all live nearby. They still refer to Bailey as "Uncle Walter."

Asay’s father resurfaced when he was in rehab, and they stayed reconnected until he died eight years later. “He wasn’t the dad I always wanted but I got to accept him for who he was,” he says. “By the time he died, there were no bad feelings.”

Asay and Bailey see each other at least every Saturday. After all they’ve been through, both together and apart, it’s difficult to envision a future where that changes.

“We’ve had this amazing journey -- growing up, playing sports and experiencing life, complete with some dark spots,” Asay says. “But to circle back around and get to a spot where we are both living our best lives now is really incredible. I’m just grateful to be able to continue this journey with my best friend.”

Do you know Walter Bailey or Matt Asay? If you’d like to reconnect, Walter can be reached at baileywalter63@gmail.com and Matt at asay2122@gmail.com

For profile comments or suggestions for future profile subjects, contact Dick Baltus: ralanbaltus@gmail.com

Member Spotlight

It had been a long time since Matt Asay had spent any quality time with the friend he’d been virtually attached at the hip to since childhood. Something like three years and change it was, but it seemed even longer to Asay, who was painfully aware of the personal struggles Walter Bailey had been going through during that time and well before it.

The two had spoken by phone, even had lunch a couple times. But after each occasion, Bailey would go quiet again, changing his phone number and slipping back into the latest dark place from which he had temporarily emerged.

And while Asay never gave up hope that he and his friend would eventually get back together for good, up to this point he hadn’t wanted to push it. He'd been working hard to conquer some demons of his own and wasn’t ready for a permanent reunion until Bailey was ready to face up to his.

But now he was feeling confident enough in the progress he'd made to believe he could be a positive influence on Bailey without himself being influenced by what his friend might be up to.

So it came to be that Asay found himself sitting in his car in front of a drug house in northeast Portland, squinting through the scorching summer sun, trying to determine if the overly thin guy heading up the street, face partially obscured by a beard and hoodie, really was the man he called his brother.

Friendly Rivals

There are infinite ways to start a lifelong friendship, and who knows how many of them involve rough housing and toy action figures. But at least one did.

Asay and Bailey met in 1978 at Sacajawea Elementary School, where the former had been enjoying his status as the unrivaled alpha-puppy of the lower grade levels right up to the day the latter swaggered in from Woodland Park.

“I was kind of a hot shot-athlete in kindergarten and first grade,” Asay remembers with a laugh. “But when Walt transfers in, it became clear pretty quickly that he was kind of a hot shot, too, and now he’s encroaching on my territory. So on the day we met, we went out on the field and had a foot race. And, of course, he blew me away.”

Despite his dominant win, Bailey saw in Asay a worthy athletic rival. But as the uncomfortable new kid in school, he also identified something more meaningful to him.

“I was a very unassuming, kind of awkward kid who’d been growing up with friends who were all black,” Bailey says. “Now I’m at a different, predominantly white school trying to forge new relationships. And I quickly saw that Matt was a kid who was, yes, athletic, but also someone who had a good influence on other kids. So, I looked up to him because of that.”

As Bailey began to settle into his new school, he became friendly enough with Asay to snag a coveted invitation to his eighth birthday party.

“I think my mom probably got some gift ideas from his mom and I wound up giving Matt a Star Wars action figure,” Bailey recalls. “I loved Star Wars, but it turned out Matt loved Star Wars even more. So, we formed an instant connection right then.”

Bailey began staying overnight at Asay’s house on a regular basis, which gave them the opportunity to cement their friendship by bouncing each other off Asay’s bedroom walls like future pro wrestlers.

“Matt had this tiny room with his bed right up against the window,” Bailey says. “We’d play tackle football in there, and to score you had to dive on the bed and touch the wall with a Nerf football. We’d give each other black eyes, knots on the head and scratches because we were both so competitive. That’s when I knew this guy was a lot like me -- only bigger. And we just became best friends.”

Which is not to say the two stopped competing against each other as they advanced through the grades regardless of the sport they were playing. And they both played most of those available to them, including football, basketball, baseball, soccer and, in Bailey’s case, track.

Oh, and roller skating, too. Can’t forget roller skating. Bailey certainly can’t.

“Matt and I would go to Skate Palace every Saturday,” he says. “All the kids from the ‘hood would go. Whenever they had couples skate, all the girls would come get Matt because he was so handsome and nice, and I was left with nothing!”

Benson or Bust

While Asay grew up a short bike ride from Madison, and both his parents were alums, he had always planned to follow two uncles to Benson. “Getting my acceptance letter there was probably one of the happiest days of my life,” he says.

Bailey was raised in the Jefferson district with a sister and four older brothers, three of whom went to Benson. Brother Tracey played with AC Green on the school’s 1981 state championship basketball team. Bailey says that, while he never felt any family pressure to go to Benson, “since my brothers went there, I had been able to see what it was about. So, I just naturally gravitated there.”

While he and Asay were happy to know they wouldn’t be separated in high school, there was an “incident” after they said goodbye to Gregory Heights Middle School that left some doubt whether they’d even be speaking to each other by the time they enrolled at Benson. Neither of them can relate the story now with a straight face, but it was no laughing matter back then.

Here’s Asay’s take on the story:

“That summer Walt and I took part in a basketball camp at Concordia College. At the conclusion of it, they held a one-on-one tournament, and we both made it to the semifinals. Now we’ve got to play each other. Everyone thought he was going to blow me away, including, I think, Walter. But I was starting to come into my own in basketball and wound up beating him. He wouldn’t talk to me for the rest of the summer.”

Now Bailey’s spin:

“Matt was smart enough to realize, if he lets me get the ball first, I’m going to out-point him. Because I could shoot. So, he gets the ball first and, because he’s taller, just backs me down and shoots over me. Over and over again. After he beats me, I ran home and cried. I was so upset. I couldn’t believe my best friend beat me one on one in front of everybody. He beat me in front of everybody!”

“He was so bent out of shape, he wouldn’t return my calls,” Asay adds. “We were going to be playing football together as freshmen, and he didn’t talk to me until maybe two weeks before daily doubles started. Then we connected and everything just melted away. He just needed some time to process not always being better than me…”

“...not being king,” Bailey interjects, laughing. “I was immature in a lot of ways, and Matt grounded me.”

Shining Stars

He jokes now about the king thing, but Bailey certainly came close to earning that status at Benson. In his earliest days in sports, Bailey’s first love had been track. But once at Benson, he identified a phenomenon that quickly had him rearranging his athletic priorities.

“I was intrigued by the people who got the most attention in sports, and football and basketball players were those people,” Bailey says, laughing.

Bailey remained committed enough to track to earn four letters and claim state championships in the long jump and as a member of Benson’s mile-relay team, but his heart belonged to football and basketball. On the field, he was named 1st Team All-PIL and All-State as both a running back and defensive back and, in basketball, he made 1st Team All-PIL as a guard.

Not one to be outdone by his friend, Asay earned three letters in football and, as a senior, 1st Team All-PIL status at tight end, defensive end and punter. That same year he made the 2nd Team All-State defensive team and played in the Shrine All-Star Game.

He captained the Benson football and basketball teams and, in baseball, was honored as a 2nd Team All-PIL outfielder and pitcher his senior year.

Through Asay’s sophomore year, basketball and baseball were his strongest sports. But that changed junior year when his football career took off and his best sports memories were made, he says.

“We had really good teams my junior and senior years,” he says. “We were 8-1 and 9-0 those two years, and junior year we won three state playoff games, which was the first time a PIL team had done that in 10 or 15 years.”

On the football field, Asay and Bailey were as connected as they were off it where, Asay says, “We were thick as thieves. Anything one of us was doing, the other was doing.”

While Bailey starred as a runner, he also could throw the ball, and Asay tried several times to talk Benson’s future PIL Hall of Fame coach Bill Dressel into taking advantage of that skill.

“I’d ask him, ‘Why don’t you let Walter throw a halfback pass? Run a sweep and let him throw it to me downfield.’ I finally talked him into doing it against Jefferson junior year, and we scored a 50-yard touchdown. From that point forward we ran that play at least once or twice a game. Senior year, I probably scored 14 touchdowns, and about half came on passes from Walter.”

Both players’ athletic success earned them multiple college scholarship offers (and, later, induction into the PIL Hall of Fame – Bailey in 2005; Asay in 2023), but not from the same schools. That meant the inseparable friends would be separated for the first time since second grade.

"I never knew which dad was coming home from work -- angry dad or happy dad. It just depended on whether he'd been drinking. He was kind of a hero, but at the same time I was terrified of him." -- Matt Asay

Out of the Light, Darkness

For all the good times they had as kids, Asay and Bailey both grew up in households that were both loving and, at times, tumultuous.

“My mom, Sharon, always encouraged me to play sports and was my biggest cheerleader growing up,” Asay says. “She worked three jobs but always made sure my sister, Amy, and I made it to practice, games and school events. She was my hero and role model. My grandparents were also very supportive and were always at my games.

“But I never knew which dad was coming home from work -- angry dad or happy dad. It just depended on whether or not he’d been drinking. He was kind of a hero, but at the same time I was terrified of him. It was a confusing situation to be in as kid. Sports were kind of an escape. I could go play ball for a couple hours and it would be the best part of my day.

“But my dad never came to any of my games. I think he had some mental health issues on top of alcoholism that made it difficult for him to be out in public. And I think he felt pretty bad about some of his choices. But it hurt when I was having a lot of success and he was nowhere to be found.”

Asay's parents divorced when he was 10 and, from his sophomore year on, he says he benefited from the love and support of his stepfather, Ken Hutchens. But while he no longer was under the influence of his father unpredictable behavior, Asay’s genetics were another matter.

“I think I knew drinking was going to be a problem in middle school,” Asay says. “That was the first time I drank, and I liked the feeling alcohol gave me. It kind of took all my insecurities away. I liked the feeling so much that I just kept drinking that first time until I got sick. After that, I didn’t drink for maybe two years. Then the next three times I drank, the same thing happened.”

That was enough to scare off Asay from alcohol for another couple years. Then came college. After accepting a scholarship offer at Portland State and starting classes, Asay says, “It was kind of an eye-opener to see people drinking in the dorms on a Tuesday night. I was like, I didn’t know you could drink on a Tuesday. That’s how drinking became part of a routine for me.”

When, after two years, Asay’s PSU football career didn’t pan out, he left school. “It started feeling like a job,” he says, "and alcohol and drugs had become more important than my education or football."

By then, he was drinking four or five days a week and, when he quit football, “that’s when I start drinking more. It wasn’t like I was drinking to get smashed, but I was drinking enough to feel OK. I called myself a functioning alcoholic. I never lost a job because of drinking, but there were many times I should have gotten in trouble.”

In 1994, Asay married a girl he’d met in the dorms at PSU. Bailey was, of course, his best man. The Asays started a family (his three sons are now 24, 26 and 29) and he continued to work on building a painting business as his drinking and drug habit grew worse.

“From the ages 23 to 36, I was an everyday drinker,” he says.

That ended in 2006 when his family stepped in.

“My mom and stepdad, my sister and her husband and my grandparents staged an intervention,” he relates. “They said, ‘If you go to inpatient rehab, we will support you the entire way. If you don't go, we’re done with you. You’re killing yourself.’ They gave me tough love, and that was my wakeup call.”

Anything That Felt Good…

In the first few years after high school, Asay and Bailey still saw each other fairly frequently, and their reunions always were an excuse to party.

“Walter partied the same way I did,” Asay says. “But I never thought I had a problem, so I never thought he had a problem.”

While his football skills had earned him scholarship offers from dozens of colleges, including every Pac-10 school, before Bailey could qualify for admission to his school of choice, the University of Washington, he had to spend a year working on his grades at Western Washington in Bellingham.

Once he got to Seattle, his stellar play helped the Huskies earn a share of the 1991 national championship and three straight trips to the Rose Bowl. The All-Pac-10 cornerback’s eight interceptions in ‘91 are still third-most in the Husky record book.

To all the world, it sure looked like Bailey had set himself up for the NFL, possibly even as a first-round draft pick. But his on-field success was hiding the reality that he was depressed and suffering from anxiety and self-doubt, some of which he attributes to what he now refers to as “trauma” at home growing up.

“I had a very loving family, but there were things going on at home that I didn’t want to tell people about,” he says. “So, I bottled it up, and then it all would come out of me when I was on a football field. That was my canvas. That’s where, athletically, I was able to recreate everything that was going on inside of me, which I now know was trauma. And my aggressiveness, being so mad when we lost, those were signs of trauma that I was releasing.

“At the time, I had no idea what trauma was, but it probably started in middle school and continued into high school, then followed me to college, where I started masking things with alcohol and drugs. They provided a temporary respite from the thoughts and feelings I was having.”

Bailey injured his shoulder in the 1993 Rose Bowl, and after performing poorly at the NFL Combine, then skipping meetings NFL teams had scheduled with him, he went undrafted. He attempted to catch on with the New York Giants as a free agent but was cut after testing positive for alcohol and marijuana.

Bailey wound up playing for the Sacramento Goldminers of the Canadian Football League in 1993, but was traded to Edmonton the next year and released four days into training camp.

Things got worse from there. In a 2015 feature story in The Seattle Times, Bailey is quoted saying, “Anything that looked good, tasted good and felt good, I was trying it. I was experimenting with anything that would make me feel numb.”

Bailey couldn’t hold a job. He and a partner had a daughter in 1996, but he was in no condition to be a father, and they moved away from him two years later.

In the months leading up to the day in 2006 when Asay entered rehab, he and Bailey were partying together several times a week. Bailey was the last person Asay saw before checking in. Still in denial about his friend's troubles, Asay says he had no idea how deep they ran until he was discharged two months later. By then, even though the fog of his denials had begun to lift, he knew he was in no position to help.

“They told us in treatment that you can’t hang out with people who are still doing the same things you used to do and expect a different result for yourself,” Asay says. “So, I didn’t reach out to Walt, and he didn’t reach out to me either. My feeling is he didn’t want to jeopardize my sobriety.”

More than three years passed before the two would see each other again.

“Walt called in 2009 and was really struggling,” Asay says. “We hung out a little bit, and it was great to see him. But he wasn’t ready to seek help. It took another year before he finally hit a bottom that was deep enough for him to say, 'I’m done. I give up. Tell me what to do'.”

The Road Back

It was Bailey, the guy walking up the street dressed for fall on a 100-degree day. He’d lost 40 or 50 pounds, and the beard was a new feature, but Asay could now see it was indeed his friend, his brother heading his way – however reluctantly.

“I just knew he was thinking, ‘He’s already spotted me; I can’t get away’,” Asay remembers.

Sometimes on prior occasions when Bailey would resurface for a call or lunch, then disappear again without a trace, he would ask his friend for a lift "home." Asay started making mental notes of Bailey’s drop-off locations.

“So, after we met up in 2009 and he ghosted me again, I went looking for him back at one of those spots,” Asay says. “Of course, it was a drug house. I actually went up and knocked on the door, but no one answered.”

So Asay went back to his car and waited until, eventually, he saw Bailey, close to unrecognizable, crest the hill.

“He came up to my window and I just said, ‘Man, I love you and I’m here for you no matter what. When you’re ready, give me a call,” Asay says.

On April 28, 2010, he was dropping his kids off at school when his phone rang and an unfamiliar number appeared on the screen. As soon as he was freed up, Asay listened to his voicemail.

“It’s Walter saying ‘Matt, I’ve finally hit bottom. I’m done. Please call’,” Asay remembers vividly. “I called immediately, got the address of this drug house he was hanging out at and told him, ‘I’ll be there in 15 minutes.’ I bolted over there and helped Walter put all his possessions into a couple garbage bags, then took him back to my place. He’s been sober ever since.”

“Once the pain got to be so great, I called my best friend and he was there for me,” Bailey says. “I’m living in an abandoned house with no lights and no food, and then he comes in and I see his smile, and we hug and I felt like all the hurt and trauma just went away.”

“It brings me to tears sometimes when I think about it,” Asay adds. “I felt like I had lost my brother. I was scared he was going to die. To have him redirect his life the way he did really feels good.”

After six months of inpatient treatment at DePaul Residential Treatment Center in Portland, Bailey graduated and started attending AA meetings and, in 2012, that’s where he and his future wife, Myka, went on their first date.

The same year, Bailey went back to DePaul, but this time as an employed resource for patients. A year later, he became a certified drug and alcohol counselor at the center, and two years after that, he joined Central City Concern, an intensive outpatient program dedicated to treating African Americans with mental health and addiction issues.

Bailey now works as an operations and policy analyst at Oregon Health Authority helping “shape policy around underserved, underprivileged and minority populations.”

He's a happy father (he reunited with his oldest daughter, Brianna, 28; a second daughter, Mya, is 17) and grandfather who is committed to “giving back” to others through his work with Dynamic Athletic Solutions, a program focused on athletes and coaches and dedicated to issues related to mental health, substance abuse and diversity.

On April 30, 2025, Bailey gratefully celebrated his 15 years of sobriety with the friend he’s counted on and looked up to since second grade. Asay will celebrate his 20th year on Jan. 12, (2026).

“If Matt didn’t get sober, I just don’t know that I ever would have,” Bailey says. “But the gift he gave me was being an example of goodness and principles and having a life worth living. He showed me that I could be someone who amounts to good.”

After selling his painting business, Asay went to work as a financial advisor in 2012 and has been with Edward Jones since 2019. A grandfather of four, Asay’s three 20-something sons (he got divorced in 2007 shortly after getting sober) all live nearby. They still refer to Bailey as "Uncle Walter."

Asay’s father resurfaced when he was in rehab, and they stayed reconnected until he died eight years later. “He wasn’t the dad I always wanted but I got to accept him for who he was,” he says. “By the time he died, there were no bad feelings.”

Asay and Bailey see each other at least every Saturday. After all they’ve been through, both together and apart, it’s difficult to envision a future where that changes.

“We’ve had this amazing journey -- growing up, playing sports and experiencing life, complete with some dark spots,” Asay says. “But to circle back around and get to a spot where we are both living our best lives now is really incredible. I’m just grateful to be able to continue this journey with my best friend.”

Do you know Walter Bailey or Matt Asay? If you’d like to reconnect, Walter can be reached at baileywalter63@gmail.com and Matt at asay2122@gmail.com

For profile comments or suggestions for future profile subjects, contact Dick Baltus: ralanbaltus@gmail.com

More On This Hall of Famer

Read about their career and accomplishments on their HoF profile page.

Other Featured Members

We have a catalog of dozens of featured members of the month.